Demonology And Devil-Lore,

Volume 2

by

Moncure Daniel Conway

First published in 1879.

Table of Contents

Chapter 3. Ahriman: The Divine Devil

Chapter 4. Viswámitra: The Theocratic Devil

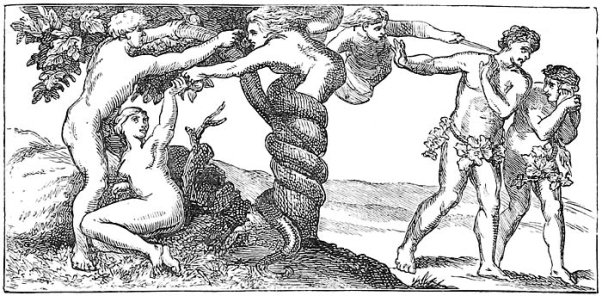

Chapter 7. Paradise and the Serpent

Chapter 13. Barbaric Aristocracy

Chapter 14. Job and the Divider

Chapter 16. Religious Despotism

Chapter 17. The Prince of this World

Chapter 18. Trial of the Great

Chapter 23. The Curse on Knowledge

Chapter 25. Faust and Mephistopheles

Chapter 29. Thoughts and Interpretations

Part 4. The Devil

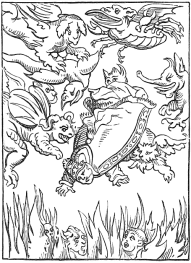

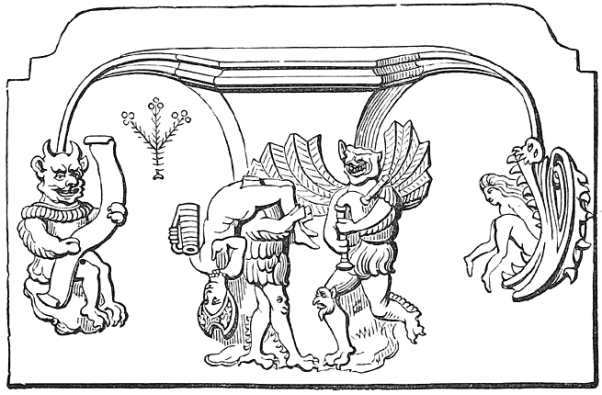

Chapter 1. Diabolism

‘We are all nothing other than Wills,’ says St. Augustine; and he adds that of the good and bad angels the nature is the same, the will different. In harmony with this John Beaumont says, ‘A good desire of mind is a good God.’[1] To which all the mythology of Evil adds, a bad desire of mind is a Devil. Every personification of an evil Will looks beyond the outward phenomena of pain, and conceives a heart that loves evil, a spirit that makes for wickedness. At this point a new element altogether enters. The physical pain incidentally represented by the Demon, generalised and organised into a principle of harmfulness in the Dragon, begins now to pass under the shadow cast by the ascending light of man’s moral nature. Man becomes conscious of moral and spiritual pains: they may be still imaginatively connected with bodily agonies, but these drop out of the immediate conception, disappear into a distant future, and are even replaced by the notion of an evil symbolised by pleasure.

The fundamental difference between either a Demon or Dragon and a Devil may be recognised in this: we never find the former voluntarily bestowing physical pleasure or happiness on man, whereas it is a chief part of the notion of a Devil that he often confers earthly favours in order to corrupt the moral nature.

There are, indeed, apparent exceptions to this theorem presented in the agatho-dragons which have already been considered in our chapter on the Basilisk; but the reader will observe that there is no intimation in such myths of any malign ulterior purpose in the good omens brought by those exceptional monsters, and that they are really forms of malevolent power whose afflictive intent is supposed to have been vanquished by the superior might of the heroes or saints to whose glory they are reluctantly compelled to become tributary.

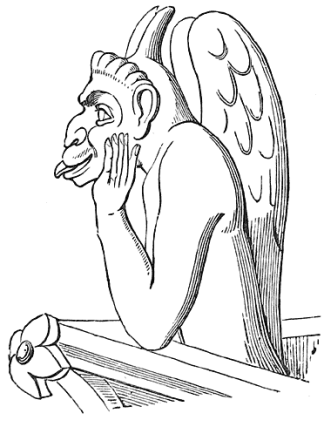

Undoubtedly the Dragon attended this moral and religious development of man’s inward nature very far, and still occupies, as at once prisoner and gaoler in the underworld, a subordinate relation to it. In the long process he has undergone certain transformations, and in particular his attribute of wings, if not derived from the notion of his struggle against holier beings, seems to have been largely enhanced thereby. The exceptional wings given to serpents in Greek art, those, for instance, which draw Demeter and Persephone in their chariot, are trifling as compared with the fully-developed wings of our conventional Dragon of the christian era. Such wings might have been developed occasionally to denote the flying cloud, the fire-breathing storm, or explain how some Ráhu was enabled to pursue the sun and moon and swallow them temporarily in the phenomena of eclipse. But these wings grew to more important dimensions when they were caught up into the Semitic conception of winged genii and destroying angels, and associated with an ambitious assault on heaven and its divine or angelic occupants.

‘There was war in Heaven,’ says the Apocalypse. The traditional descriptions of this war follow pretty closely, in dramatic details, other and more ancient struggles which reflect man’s encounters with the hardships of nature. In those encounters man imagined the gods descending earthward to mingle in the fray; but even where the struggle mounted highest the scenery is mainly terrestrial and the issues those of place and power, the dominion of visible Light established above Darkness, or of a comparatively civilised over a savage race. The wars between the Devas and Asuras in India, the Devs and Ahuras in Persia, Buddha and the Nagas in Ceylon, Garúra and the Serpent-men in the north of India, gods and Frost-giants in Scandinavia, still concern man’s relation to the fruits of the earth, to heat and frost, to darkness or storm and sunshine.

But some of these at length find versions which reveal their tendency towards spiritualisation. The differences presented by one of these legends which has survived among us in nearly its ancient form from the same which remains in a partly mystical form will illustrate the transitional phase. Thus, Garúra expelling the serpents from his realm in India is not a saintly legend; this exterminator of serpents is said to have compelled the reptile race to send him one of their number daily that he might eat it, and the rationalised tradition interprets this as the prince’s cannibalism. The expulsion of Nagas or serpents from Ceylon by Buddha, in order that he might consecrate that island to the holy law, marks the pious accentuation of the fable. The expulsion of snakes from Ireland by St. Patrick is a legend conceived in the spirit of the curse pronounced upon the serpent in Eden, but in this case the modern myth is the more primitive morally, and more nearly represents the exploit of Garúra. St. Patrick expels the snakes that he may make Ireland a paradise physically, and establish his reputation as an apostle by fulfilling the signs of one named by Christ;[2] and in this particular it slightly rises above the Hindu story. In the case of the serpent cursed in Eden a further moralisation of the conflict is shown. The serpent is not present in Eden, as in the realms of Garúra and St. Patrick, for purposes of physical devastation or pain, but to bestow a pleasure on man with a view to success in a further issue between himself and the deity. Yet in this Eden myth the ancient combat is not yet fairly spiritualised; for the issue still relates, as in that between the Devas and Asuras, to the possession of a magical fruit which by no means confers sanctity. In the apocalyptic legend of the war in heaven,[3] the legend has become fairly spiritualised. The issue is no longer terrestrial, it is no longer for mere power; the Dragon is arrayed against the woman and child, and against the spiritual ‘salvation’ of mankind, of whom he is ‘accuser’ and ‘deceiver.’

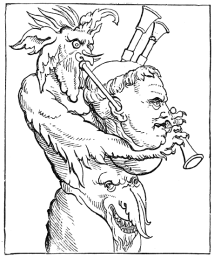

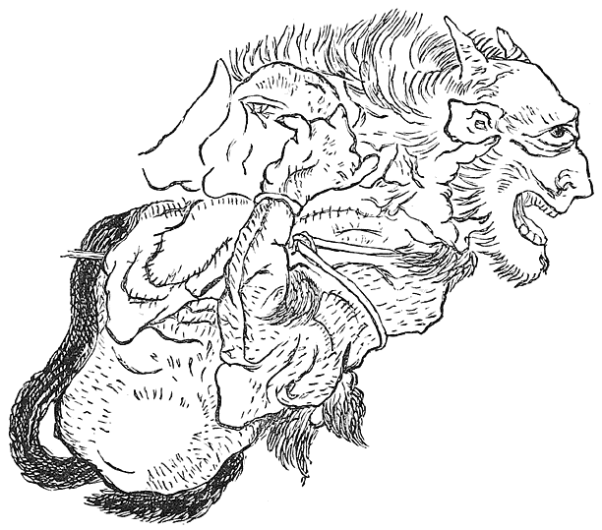

Surely nobody could be ‘deceived’ by ‘a great fiery-red Dragon, having seven heads and ten horns’! In this vision the Dragon is pressed as far as the form can go in the symbolisation of evil. To devour the child is its legitimate work, but as ‘accuser of the brethren before God day and night’ the monstrous shape were surely out of place by any mythologic analogy; and one could hardly imagine such a physiognomy capable of deceiving ‘the whole world.’ It is not wonderful, therefore, that the Dragon’s presence in heaven is only mentioned in connection with his fall from it. It is significant that the wings are lost in this fall; for while his ‘angelic’ relationship suggests the previous wings, the woman is able to escape the fallen monster by the two wings given her.[4] Wingless now, ‘the old serpent’ once more, the monster’s shape has no adaptation to the moral and religious struggle which is to ensue. For his shape is a method, and it means the perfection of brute force. That, indeed, also remains in the sequel of this magnificent myth. As in the legend of the Hydra two heads spring up in place of that which falls, so in this Christian legend out of the overthrown monster, henceforth himself concealed, two arise from his inspiration,—the seven-headed, ten-horned Beast who continues the work of wrath and pain; but also a lamb-like Beast, with only two horns (far less terrible), and able to deceive by his miracles, for he is even able to call down fire from heaven. The ancient Serpent-dragon, the expression of natural pain, thus goes to pieces. His older part remains to work mischief and hurt; and the cry is uttered, ‘Be merry, ye heavens, and ye that tabernacle in them: woe to the earth and the sea! for the devil is come down unto you, having great wrath because he knows that he has a short time.’[5] But there is a lamb-like part of him too, and his relation to the Dragon is only known by his voice.

This subtle adaptation of the symbol of external pain to the representation of the moral struggle, wherein the hostile power may assume deceptive forms of beauty and pleasure, is only one impressive illustration of the transfer of human conceptions of evil from outward to inward nature. The transition is from a malevolent, fatal, principle of harmfulness to the body to a malevolent, fatal, principle of evil to the conscience. The Demon was natural; the Dragon was both physical and metaphysical; the Devil was and is theological. In the primitive Zoroastrian theology, where the Devil first appears in clear definition, he is the opponent of the Good Mind, and the combat between the two, Ormuzd and Ahriman, is the spiritualisation of the combat between Light and Darkness, Pain and Happiness, in the external world. As these visible antagonists were supposed to be exactly balanced against each other, so are their spiritual correlatives. The Two Minds are described as Twins.

‘Those old Spirits, who are twins, made known what is good and what is evil in thoughts, words, and deeds. Those who are good distinguished between the two; not so those who are evil-doers.

‘When these two Spirits came together they made first life and death, so that there should be at last the most wretched life for the bad, but for the good blessedness.

‘Of these two Spirits the evil one chose the worst deeds; the kind Spirit, he whose garment is the immovable sky, chose what is right.’[6]

This metaphysical theory follows closely the primitive scientific observations on which it is based; it is the cold of the cold, the gloom of the darkness, the sting of death, translated into some order for the intellect which, having passed through the Dragon, we find appearing in this Persian Devil; and against his blackness the glory of the personality from whom all good things proceed shines out in a splendour no longer marred by association with the evil side of nature. Ormuzd is celebrated as ‘father of the pure world,’ who sustains ‘the earth and the clouds that they do not fall,’ and ‘has made the kindly light and the darkness, the kindly sleep and the awaking;’[7] at every step being suggested the father of the impure world, the unkindly light, darkness or sleep.

The ecstasy which attended man’s first vision of an ideal life defied the contradictory facts of outward and inward nature. So soon as he had beheld a purer image of himself rising above his own animalism, he must not only regard that animalism as an instigation of a devil, but also the like of it in nature; and this conception will proceed pari passu with the creation of pure deities in the image of that higher self. There was as yet no philosophy demanding unity in the Cosmos, or forbidding man to hold as accursed so much of nature as did not obviously accord with his ideals.

Mr. Edward B. Tylor has traced the growth of Animism from man’s shadow and his breathing; Sir John Lubbock has traced the influence of dreams in forming around him a ghostly world; Mr. Herbert Spencer has given an analysis of the probable processes by which this invisible environment was shaped for the mental conception in accordance with family and social conditions. But it is necessary that we should here recognise the shadow that walked by the moral nature, the breathings of religious aspiration, and the dreams which visited a man whose moral sense was so generally at variance with his animal desires. The code established for the common good, while necessarily having a relation to every individual conscience, is a restriction upon individual liberty. The conflict between selfishness and duty is thus inaugurated; it continues in the struggle between the ‘law in the members and the law in the spirit,’ which led Paul to beat his body (ὑποπιαξομαί) to keep it in subjection; it passes from the Latin poet to the Englishman, who turns his experience to a rune—

I see the right, and I approve it too;

Condemn the wrong, and yet the wrong pursue.

As the light which cast it was intense, even so intense was the shadow it cast beneath all it could not penetrate. Passionate as was the saintliest man’s love of good, even so passionate was his spiritual enemy’s love of evil. High as was the azure vault that mingled with his dreams of purity, so deep was the abyss beneath his lower nature. The superficial equalities of phenomena, painful and pleasurable, to his animal nature had cast the mould into which his theories of the inward and the moral phenomena must be cast; and thus man—in an august moment—surrendered himself to the dreadful conception of a supreme Principle of Wickedness: wherever good was there stood its adversary; wherever truth, there its denier; no light shone without the dark presence that would quench it; innocence had its official accuser, virtue its accomplished tempter, peace its breaker, faith its disturber and mocker. Nay, to this impersonation was added the last feature of fiendishness, a nature which found its supreme satisfaction in ultimately torturing human beings for the sins instigated by himself.

It is open to question how far any average of mankind really conceived this theological dogma. Easy as it is to put into clear verbal statement; readily as the analogies of nature supply arguments for and illustrations of a balance between moral light and darkness, love and hatred; yet is man limited in subjective conceptions to his own possibilities, and it may almost be said that to genuinely believe in an absolute Fiend a man would have to be potentially one himself. But any human being, animated by causeless and purposeless desire to inflict pain on others, would be universally regarded as insane, much more one who would without motive corrupt as well as afflict.

Even theological statements of the personality of Evil, and what that implies, are rare. The following is brave enough to be put on record, apart from its suggestiveness.

‘It cannot be denied that as there is an inspiration of holy love, so is there an inspiration of hatred, or frantic pleasure, with which men surrender themselves to the impulses of destructiveness; and when the popular language speaks of possessions of Satan, of incarnate devils, there lies at the bottom of this the grave truth that men, by continued sinning, may pass the ordinary limit between human and diabolic depravity, and lay open in themselves a deep abyss of hatred which, without any mixture of self-interest, finds its gratification in devastation and woe.’[8]

On this it may be said that the popular commentary on cases of the kind is contained in the very phrase alluded to, ‘possession,’—the implication being that such disinterested depravity is nowise possible within the range of simple human experience,—and, in modern times, ‘possessions’ are treated in asylums. Morbid conditions, however, are of such varied degrees that it is probable many have imagined a Being in whom their worst impulses are unrestrained, and thus there have been sufficient popular approximations to an imaginative conception of a Devil to enable the theological dogma, which few can analyse, to survive.

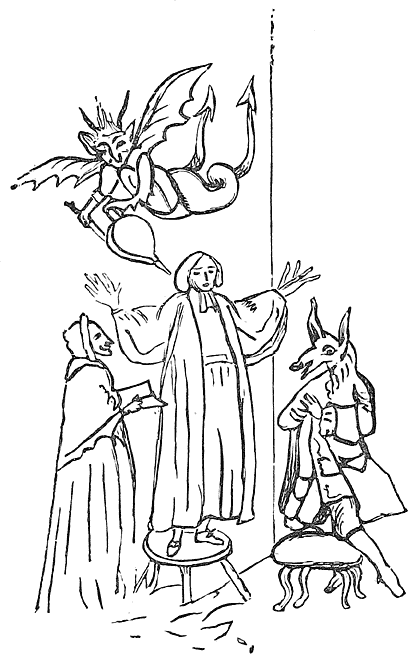

It must not be supposed, however, that the moral and spiritual ideals, to which allusion has just been made, are normally represented in the various Devils which we have to consider. It is the characteristic of personifications, whether celestial or infernal, to supersede gradually the ideas out of which they spring. As in the fable of Agni, who is said to have devoured his parents when he was born, a metaphor of fire consuming the two sticks which produce it, religious history shows both deities and devils, by the flame of personal devotion or hatred they engender, burning up the ideas that originate them. When instead of unconscious forces and inanimate laws working to results called good and evil, men see great personal Wills engaged in personal conflict, the universe becomes a government of combat; the stars of heaven, the angels and the imps, men and women, the very plants and animals, are caught up in the battle, to be marshalled on one side or the other; and in the military spirit and fury of the struggle the spiritual ideals become as insignificant beneath the phantom-hosts they evoked as the violets and daisies which an army tramples in its march. There is little difference at last between the moral characteristics of the respective armies of Ormuzd and Ahriman, Michael and Satan; their strategy and ferocity are the same.[9] Wherever the conception is that of a universe divided into hostile camps, the appropriate passions are kindled, and in the thick of the field, where Cruelty and Gentleness met, is seen at last a horned Beast confronted by a horned Lamb.[10] On both sides is exaltation of the horn.

We need only look at the outcome of the gentle and lowly Jesus through the exigencies of the church militant to see how potent are such forces. Although lay Christians of ordinary education are accustomed to rationalise their dogmas as well as they can, and dwell on the loving and patient characteristics of Jesus, the horns which were attached to the brow of him who said, ‘Love your enemies’ by ages of Christian warfare remain still in the Christ of Theology, and they are still depended on to overawe the ‘sinner.’ In an orthodox family with which I have had some acquaintance, a little boy, who had used naughty expressions of resentment towards a playmate was admonished that he should be more like Christ, ‘who never did any harm to his enemies.’ ‘No,’ answered the wrathful child, ‘but he’s a-going to.’

As in Demonology we trace the struggles of man with external obstructions, and the phantasms in which these were reflected until they were understood or surmounted, we have now to consider the forms which report human progression on a higher plane,—that of social, moral, and religious evolution. Creations of a crude Theology, in its attempt to interpret the moral sentiment, the Devils to which we now turn our attention have multiplied as the various interests of mankind have come into relations with their conscience. Every degree of ascent of the moral nature has been marked by innumerable new shadows cast athwart the mind and the life of man. Every new heaven of ideas is followed by a new earth, but ere this conformity of things to thoughts can take place struggles must come and the old demons will be recalled for new service. As time goes on things new grow old; the fresh issues pass away, their battlefields grow cold; then the brood of superstition must flit away to the next field where carrion is found. Foul and repulsive as are these vultures of the mind—organisms of moral sewage—every one of them is a witness to the victories of mankind over the evils they shadow, and to the steady advance of a new earth which supplies them no habitat but the archæologist’s page.

Chapter 2. The Second Best

A lady residing in Hampshire, England, recently said to a friend of the present writer, both being mothers, ‘Do you make your children bow their heads whenever they mention the Devil’s name? I do,’ she added solemnly,—‘I think it’s safer.’

This instance of reverence for the Devil’s name, occurring in a respectable English family, may excite a smile; but if my reader has perused the third and fourth chapters (Part I.) of this work, in which it was necessary to state certain facts and principles which underlie the phenomena of degradation in both Demonology and Devil-lore, he will already know the high significance of nearly all the names which have invested the personifications of evil; and he will not be surprised to find their original sanctity, though lowered, sometimes, surviving in such imaginary forms after the battles in which they were vanquished have passed out of all contemporary interest. If, for example, instead of the Devil, whose name is uttered with respect in the Hampshire household, any theological bogey of our own time were there mentioned, such as ‘Atheist,’ it might hardly receive such considerate treatment.

The two chapters just referred to anticipate much that should be considered at this point of our inquiry. It is only necessary here to supplement them with a brief statement, and to some extent a recapitulation, of the processes by which degraded deities are preserved to continue through a structural development and fulfil a necessary part in every theological scheme which includes the conception of an eternal difference between good and evil.

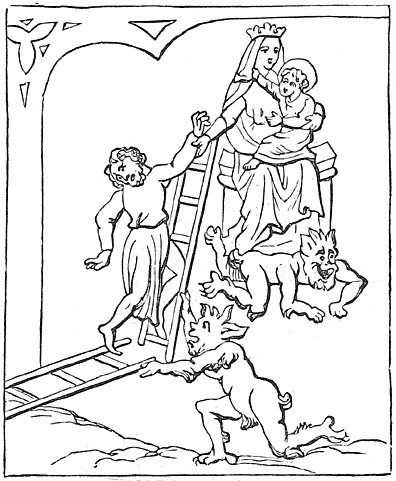

Every personification when it first appears expresses a higher and larger view. When deities representing the physical needs of mankind have failed, as they necessarily must, to meet those needs, atheism follows, though it cannot for a long time find philosophical expression. It is an atheism ad hoc, so to say, and works by degrading particular gods instead of by constructing antitheistic theories. Successive dynasties of deities arise and flourish in this way, each representing a less arbitrary relation to nature,—peril lying in that direction,—and a higher moral and spiritual ideal, this being the stronghold of deities. It is obvious that it is far easier to maintain the theory that prayers are heard and answered by a deity if those prayers are limited to spiritual requests, than when they are petitions for outward benefits. By giving over the cruel and remorseless forces of nature to the Devil,—i.e., to this or that personification of them who, as gods, had been appealed to in vain to soften such forces,—the more spiritual god that follows gains in security as well as beauty what he surrenders of empire and omnipotence. This law, illustrated in our chapter on Fate, operates with tremendous effect upon the conditions under which the old combat is spiritualised.

An eloquent preacher has said:—‘Hawthorne’s fine fancy of the youth who ascribed heroic qualities to the stone face on the brow of a cliff, thus converting the rocky profile into a man, and, by dint of meditating on it with admiring awe, actually transferred to himself the moral elements he worshipped, has been made fact a thousand times, is made fact every day, by earnest spirits who by faithful longing turn their visions into verities, and obtain live answers to their petitions to shadows.’[11]

However imaginary may be the benedictions so derived by the worshipper from his image, they are most real as they redound to the glory and power of the image. The crudest personification, gathering up the sanctities of generations, associated with the holiest hopes, the best emotions, the profoundest aspirations of human nature, may be at length so identified with these sentiments that they all seem absolutely dependent upon the image they invest. Every criticism of such a personification then seems like a blow aimed at the moral laws. If educated men are still found in Christendom discussing whether morality can survive the overthrow of such personifications, and whether life were worth living without them, we may readily understand how in times when the social, ethical, and psychological sciences did not exist at all, all that human beings valued seemed destined to stand or fall with the Person supposed to be their only keystone.

But no Personage, however highly throned, can arrest the sun and moon, or the mind and life of humanity. With every advance in physical or social conditions moral elements must be influenced; every new combination involves a recast of experiences, and presently of convictions. Henceforth the deified image can only remain as a tyrant over the heart and brain which have created it,—

Creatura a un tempo

E tiranno de l’uom, da cui soltanto

Ebbe nomi ed aspetti e regno e altari.[12]

This personification, thus ‘at once man’s creature and his tyrant,’ is objectively a name. But as it has been invested with all that has been most sacred, it is inevitable that any name raised against it shall be equally associated with all that has been considered basest. This also must be personified, for the same reason that the good is personified; and as names are chiefly hereditary, it pretty generally happens that the title of some fallen and discredited deity is advanced to receive the new anathema. But what else does he receive? The new ideas; the growing ideals and the fresh enthusiasms are associated with some fantastic shape with anathematised name evoked from the past, and thus a portentous situation is reached. The worshippers of the new image will not accept the bad name and its base associations; they even grow strong enough to claim the name and altars of the existing order, and give battle for the same. Then occurs the demoralisation, literally speaking, of the older theology. The personification reduced to struggle for its existence can no longer lay emphasis upon the moral principles it had embodied, these being equally possessed by their opponents; nay, its partisans manage to associate with their holy Name so much bigotry and cruelty that the innovators are at length willing to resign it. The personal loyalty, which is found to continue after loyalty to principles has ceased, proceeds to degrade the virtues once reverenced when they are found connected with a rival name. ‘He casteth out devils through Beelzebub’ is a very ancient cry. It was heard again when Tertullian said, ‘Satan is God’s ape.’ St. Augustine recognises the similarity between the observances of Christians and pagans as proving the subtle imitativeness of the Devil; the phenomena referred to are considered elsewhere, but, in the present connection, it may be remarked that this readiness to regard the same sacrament as supremely holy or supremely diabolical as it is celebrated in honour of one name or another, accords closely with the reverence or detestation of things more important than sacraments, as they are, or are not, consecrated by what each theology deems official sanction. When sects talk of ‘mere morality’ we may recognise in the phrase the last faint war-cry of a god from whom the spiritual ideal has passed away, and whose name even can survive only through alliance with the new claimant of his altars. While the new gods were being called devils the old ones were becoming such.

The victory of the new ideal turns the old one to an idol. But we are considering a phase of the world when superstition must invest the new as well as the old, though in a weaker degree. A new religious system prevails chiefly through its moral superiority to that it supersedes; but when it has succeeded to the temples and altars consecrated to previous divinities, when the ardour of battle is over and conciliation becomes a policy as well as a virtue, the old idol is likely to be treated with respect, and may not impossibly be brought into friendly relation with its victorious adversary. He may take his place as ‘the second best,’ to borrow Goethe’s phrase, and be assigned some function in the new theologic régime. Thus, behind the simplicity of the Hampshire lady instructing her children to bow at mention of the Devil’s name, stretch the centuries in which Christian divines have as warmly defended the existence of Satan as that of God himself. With sufficient reason: that infernal being, some time God’s ‘ape’ and rival, was necessarily developed into his present position and office of agent and executioner under the divine government. He is the great Second Best; and it is a strange hallucination to fancy that, in an age of peaceful inquiry, any divine personification can be maintained without this patient Goat, who bears blame for all the faults of nature, and who relieves divine Love from the odium of supplying that fear which is the mother of devotion,—at least in the many millions of illogical eyes into which priests can still look without laughing.

Such, in brief outline, has been the interaction of moral and intellectual forces operating within the limits of established systems, and of the nations governed by them. But there are added factors, intensifying the forces on each side, when alien are brought into rivalry and collision with national deities. In such a contest, besides the moral and spiritual sentiments and the household sanctities, which have become intertwined with the internal deities, national pride is also enlisted, and patriotism. But on the other side is enlisted the charm of novelty, and the consciousness of fault and failure in the home system. Every system imported to a foreign land leaves behind its practical shortcomings, puts its best foot forward—namely, its theoretical foot—and has the advantage of suggesting a way of escape from the existing routine which has become oppressive. Napoleon I. said that no people profoundly attached to the institutions of their country can be conquered; but what people are attached to the priestly system over them? That internal dissatisfaction which, in secular government, gives welcome to a dashing Corsican or a Prince of Orange, has been the means of introducing many an alien religion, and giving to many a prophet the honour denied him in his own country. Buddha was a Hindu, but the triumph of his religion is not in India; Zoroaster was a Persian, but there are no Parsees in Persia; Christianity is hardly a colonist even in the native land of Christ.

These combinations and changes were not effected without fierce controversies, ferocious wars, or persecutions, and the formation of many devils. Nothing is more normal in ancient systems than the belief that the gods of other nations are devils. The slaughter of the priests of Baal corresponds with the development of their god into Beelzebub. In proportion to the success of Olaf in crushing the worshippers of Odin, their deity is steadily transformed to a diabolical Wild Huntsman. But here also the forces of partial recovery, which we have seen operating in the outcome of internal reform, manifest themselves; the vanquished, and for a time outlawed deity, is, in many cases, subsequently conciliated and given an inferior, and, though hateful, a useful office in the new order. Sometimes, indeed, as in the case of the Hindu destroyer Siva, it is found necessary to assign a god, anathematised beyond all power of whitewash, to an equal rank with the most virtuous deity. Political forces and the exigencies of propagandism work many marvels of this kind, which will meet us in the further stages of our investigation.

Every superseded god who survives in subordination to another is pretty sure to be developed into a Devil. Euphemism may tell pleasant fables about him, priestcraft may find it useful to perpetuate belief in his existence, but all the evils of the universe, which it is inconvenient to explain, are gradually laid upon him, and sink him down, until nothing is left of his former glory but a shining name.

Chapter 3. Ahriman: The Divine Devil

Any one who has witnessed Mr. Henry Irving’s scholarly and masterly impersonation of the character of Louis XI. has had an opportunity of recognising a phase of superstition which happily it were now difficult to find off the stage. Nothing could exceed the fine realism with which that artist brought before the spectator the perfected type of a pretended religion from which all moral features have been eliminated by such slow processes that the final success is unconsciously reached, and the horrible result appears unchecked by even any affectation of actual virtue. We see the king at sound of a bell pausing in his instructions for a treacherous assassination to mumble his prayers, and then instantly reverting to the villany over whose prospective success he gloats. In the secrecy of his chamber no mask falls, for there is no mask; the face of superstition and vice on which we look is the real face which the ages of fanaticism have transmitted to him.

Such a face has oftener been that of a nation than that of an individual, for the healthy forces of life work amid the homes and hearts of mankind long before their theories are reached and influenced. Such a face it was against which the moral insurrection which bears the name of Zoroaster arose, seeing it as physiognomy of the Evil Mind, naming it Ahriman, and, in the name of the conscience, aiming at it the blow which is still felt across the centuries.

Ingenious theorists have accounted for the Iranian philosophy of a universal war between Ormuzd (Ahuramazda) the Good, and Ahriman (Angromainyus) the Evil, by vast and terrible climatic changes, involving extremes of heat and cold, of which geologists find traces about Old Iran, from which a colony of Aryans migrated to New Iran, or Persia. But although physical conditions of this character may have supplied many of the metaphors in which the conflict between Good and Evil is described in the Avesta, there are other characteristics of that ancient scripture which render it more probable that the early colonisation of Persia was, like that of New England, the result of a religious struggle. Some of the gods most adored in India reappear as execrated demons in the religion of Zoroaster; the Hindu word for god is the Parsî word for devil. These antagonisms are not merely verbal; they are accompanied in the Avesta with the most furious denunciations of theological opponents, whom it is not difficult to identify with the priests and adherents of the Brahman religion.

The spirit of the early scriptures of India leaves no room for doubt as to the point at which this revolution began. It was against pious Privilege. The saintly hierarchy of India were a caste quite irresponsible to moral laws. The ancient gods, vague names for the powers of nature, were strictly limited in their dispensations to those of their priests;[13] and as to these priests the chief necessities were ample offerings, sacrifices, and fulfilment of the ceremonial ordinances in which their authority was organised, these were the performances rewarded by a reciprocal recognition of authority. To the image of this political régime, theology, always facile, accommodated the regulations of the gods. The moral law can only live by being supreme; and as it was not supreme in the Hindu pantheon, it died out of it. The doctrine of ‘merits,’ invented by priests purely for their own power, included nothing meritorious, humanly considered; the merits consisted of costly sacrifices, rich offerings to temples, tremendous penances for fictitious sins, ingeniously devised to aggrandise the penances which disguised power, and prolonged austerities that might be comfortably commuted by the wealthy. When this doctrine had obtained general adherence, and was represented by a terrestrial government corresponding to it, the gods were necessarily subject to it. That were only to say that the powers of nature were obedient to the ‘merits’ of privileged saints; and from this it is an obvious inference that they are relieved from moral laws binding on the vulgar.

The legends which represent this phase of priestly dominion are curiously mixed. It would appear that under the doctrine of ‘merits’ the old gods declined. Such appears to be the intimation of the stories which report the distress of the gods through the power of human saints. The Rajah Ravana acquired such power that he was said to have arrested the sun and moon, and so oppressed the gods that they temporarily transformed themselves to monkeys in order to destroy him. Though Viswámitra murders a saint, his merits are such that the gods are in great alarm lest they become his menials; and the completeness, with which moral considerations are left out of the struggle on both sides is disclosed in the item that the gods commissioned a nymph to seduce the saintly murderer, and so reduce a little the force of his austerities. It will be remembered that the ancient struggle of the Devas and Asuras was not owing to any moral differences, but to an alleged unfair distribution of the ambrosia produced by their joint labours in churning the ocean. The fact that the gods cheated the demons on that occasion was never supposed to affect the supremacy they acquired by the treachery; and it could, therefore, cause no scandal when later legends reported that the demons were occasionally able to take gods captive by the practice of these wonderful ‘merits’ which were so independent of morals. One Asura is said to have gained such power in this way that he subjugated the gods, and so punished them that Siva, who had originally endowed that demon, called into being Scanda, a war-god, to defend the tortured deities. The most ludicrous part of all is that the gods themselves were gradually reduced to the necessity of competing like others for these tremendous powers; thus the Bhagavat Purana states that Brahma was enabled to create the universe by previously undergoing penance for sixteen thousand years.

The legends just referred to are puranic, and consequently of much later date than the revolution traceable in the Iranian religion; but these later legends are normal growths from vedic roots. These were the principles of ancient theology, and the foundation of priestly government. In view of them we need not wonder that Hindu theology devised no special devil; almost any of its gods might answer the purposes of one. Nor need we be surprised that it had no particular hell; any society organised by the sanctions of religion, but irresponsible to its moral laws, would render it unnecessary to look far for a hell.

From this cosmological chaos the more intelligent Hindus were of course liberated; but the degree to which the fearful training had corrupted the moral tissues of those who had been subjected to it was revealed in the bald principle of their philosophers, that the superstition must continue to be imposed on the vulgar, whilst the learned might turn all the gods into a scientific terminology.

The first clear and truthful eye that touched that system would transform it from a Heaven to an Inferno. So was it changed under the eye of Zoroaster. That ancient pantheon which had become a refuge for all the lies of the known world; whose gods were liars and their supporters liars; was now turned into a realm of organised disorder, of systematised wrong; a vast creation of wickedness, at whose centre sat its creator and inspirer, the immoral god, the divine devil—Ahriman.

It is indeed impossible to ascertain how far the revolt against the old Brahmanic system was political. It is, of course, highly improbable that any merely speculative system would excite a revolution; but at the same time it must be remembered that, in early days, an importance was generally attached to even abstract opinions such as we still find among the superstitious who regard an atheistic sentiment as worse than a theft. However this may have been, the Avesta does not leave us in any doubt as to the main fact,—namely, that at a certain time and place man came to a point where he had to confront antagonism to fundamental moral principles, and that he found the so-called gods against him. In the establishment of those principles priests recognised their own disestablishment. What those moral laws that had become necessary to society were is also made clear. ‘We worship the Pure, the Lord of Purity!’ ‘We honour the good spirit, the good kingdom, the good law,—all that is good.’ ‘Evil doctrine shall not again destroy the world.’ ‘Good is the thought, good the word, good the deed, of the pure Zarathustra.’ ‘In the beginning the two heavenly Ones spoke—the Good to the Evil—thus: Our souls, doctrines, words, works, do not unite together.’ These sentences are from the oldest Gâthâs of the Avesta.

The following is a very ancient Gâthâ:—‘All your Devas (Hindu ‘gods’) are only manifold children of the Evil Mind, and the great One who worships the Saoma of lies and deceits; besides the treacherous acts for which you are notorious in the Seven Regions of the earth. You have invented all the evil that men speak and do, which is indeed pleasant to the Devas, and is devoid of all goodness, and therefore perishes before the insight of the truth of the wise. Thus you defraud men of their good minds and of their immortality by your evil minds—as well by those of the Devas as through that of the Evil Spirit—through evil deeds and evil words, whereby the power of liars grows.

‘1. Come near, and listen to the wise sayings of the omniscient, the songs in praise of the Living One, and the prayers of the Good Spirit, the glorious truths whose origin is seen in the flames.

‘2. Listen, therefore, to the Earth spirit—Look at the flames with reverent mind. Every one, man and woman, is to be distinguished according to his belief. Ye ancient Powers, watch and be with us!

‘3. From the beginning there were two Spirits, each active in itself. They are the good and the bad in thought, word, and deed. Choose ye between them: do good, not evil!

‘4. And these two Spirits meet and create the first existence, the earthy, that which is and that which is not, and the last, the spiritual. The worst existence is for the liars, the best for the truthful.

‘5. Of these two spirits choose ye one, either the lying, the worker of Evil, or the true holiest spirit. Whoso chooses the first chooses the hardest fate; whoso the last, honours Ahuramazda in faith and in truth by his deeds.

‘6. Ye cannot serve both of these two. An evil spirit whom we will destroy surprises those who deliberate, saying, Choose the Evil Mind! Then do those spirits gather in troops to attack the two lives of which the prophets prophesy.

‘7. And to this earthly life came Armaiti with earthly power to help the truth, and the good disposition: she, the Eternal, created the material world, but the Spirit is with thee, O Wise One! the first of creations in time.

‘8. When any evil falls upon the spirit, thou, O Wise One, givest temporal possessions and a good disposition; but him whose promises are lies, and not truth, thou punishest.’

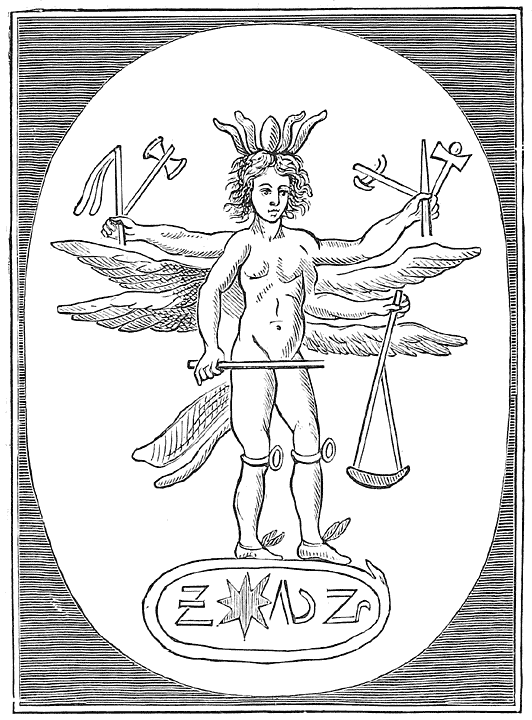

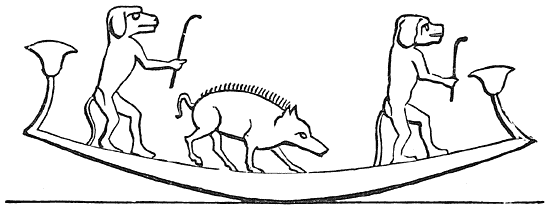

Around the hymns of the Avesta gradually grew a theology and a mythology which were destined to exert a powerful influence on the world. These are contained in the Bundehesch.[14] Anterior to all things and all beings was Zeruane-Akrene (‘Boundless Time’), so exalted that he can only be worshipped in silence. From him emanated two Ferouers, spiritual types, which took form in two beings, Ormuzd and Ahriman. These were equally pure; but Ahriman became jealous of his first-born brother, Ormuzd. To punish Ahriman for his evil feeling, the Supreme Being condemned him to 12,000 years’ imprisonment in an empire of rayless Darkness. During that period must rage the conflict between Light and Darkness, Good and Evil. As Ormuzd had his pre-existing type or Ferouer, so by a similar power—much the same as the Platonic Logos or Word—he created the pure or spiritual world, by means of which the empire of Ahriman should be overthrown. On the earth (still spiritual) he raised the exceeding high mountain Albordj, Elburz (snow mountain),[15] on whose summit he fixed his throne; whence he stretched the bridge Chinevat, which, passing directly over Duzhak, the abyss of Ahriman (or hell), reaches to the portal of Gorodman, or heaven. All this was but a Ferouer world—a prototype of the material world. In anticipation of its incorporation in a material creation, Ormuzd (by emanations) created in his own image six Amshaspands, or agents, of both sexes, to be models of perfection to lower spirits—and to mankind, when they should be created—and offer up their prayers to himself. The second series of emanations were the Izeds, benevolent genii and guardians of the world, twenty-eight in number, of whom the chief is Mithras, the Mediator. The third series of emanations were the innumerable Ferouers of things and men—for each must have its soul, which shall purify them in the day of resurrection. In antagonism to all these, Ahriman produced an exactly similar host of dark and evil powers. These Devas rise, rank on rank, to their Arch-Devs—each of whom is chained to his planet—and their head is Ash-Mogh, the ‘two-footed serpent of lies,’ who seems to correspond to Mithras, the divine Mediator.

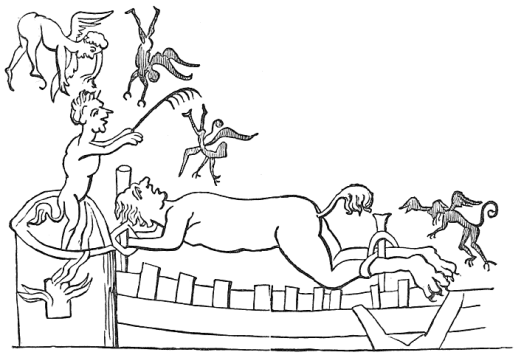

After a reign of 3000 years Ormuzd entered on the work of realising his spiritual emanations in a material universe. He formed the sun as commander-in-chief, the moon as his lieutenant, the planets as captains of a great host—the stars—who were soldiers in his war against Ahriman. The dog Sirius he set to watch at the bridge Chinevat (the Milky Way), lest thereby Ahriman should scale the heavens. Ormuzd then created earth and water, which Ahriman did not try to prevent, knowing that darkness was inherent in these. But he struck a blow when life was produced. This was in form of a Bull, and Ahriman entered it and it perished; but on its destruction there came out of its left shoulder the seed of all clean and gentle animals, and, out of its right shoulder—Man.

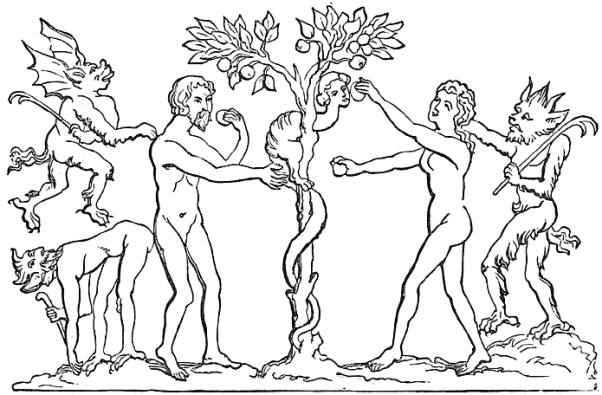

Ahriman had matched every creation thus far; but to make man was beyond his power, and he had no recourse but to destroy him. However, when the original man was destroyed, there sprang from his body a tree which bore the first human pair, whom Ahriman, however, corrupted in the manner elsewhere described.

It is a very notable characteristic of this Iranian theology, that although the forces of good and evil are co-extensive and formally balanced, in potency they are not quite equal. The balance of force is just a little on the side of the Good Spirit. And this advantage appears in man. Zoroaster said, ‘No earthly man with a hundredfold strength does so much evil as Mithra with heavenly strength does good;’ and this thought reappears in the Parsî belief that the one part of paradisiac purity, which man retained after his fall, balances the ninety-nine parts won by Ahriman, and in the end will redeem him. For this one divine ray preserved enables him to receive and obey the Avesta, and to climb to heaven by the stairway of three vast steps—pure thought, pure word, pure deed. The optimistic essence of the mythology is further shown in the belief that every destructive effort of Ahriman resulted in a larger benefit than Ormuzd had created. The Bull (Life) destroyed, man and animal sprang into being; the man destroyed, man and woman appeared. And so on to the end. In the last quarter of the 12,000 years for which Ahriman was condemned, he rises to greater power even than Ormuzd, and finally he will, by a fiery comet, set the visible universe in conflagration; but while this scheme is waxing to consummation Ormuzd will send his holy Prophet Sosioch, who will convert mankind to the true law,[16] so that when Ahriman’s comet consumes the earth he will really be purifying it. Through the vast stream of melted metals and minerals the righteous shall pass, and to them it will be as a bath of warm milk: the wicked in attempting to pass shall be swept into the abyss of Duzhak; having then suffered three days and nights, they shall be raised by Ormuzd refined and purified. Duzhak itself shall be purified by this fire, and last of all Ahriman himself shall ascend to his original purity and happiness. Then from the ashes of the former world shall bloom a paradise that shall remain for ever.

In this system it is notable that we find the monster serpent of vedic mythology, Ahi, transformed into an infernal region, Duzhak. The dragon, being a type of physical suffering, passes away in Iranian as in the later Semitic mythology before the new form, which represents the stings of conscience though it may be beneath external pleasure. In this respect, therefore, Ahriman fulfils the definition of a devil already given. In the Avesta he fulfils also another condition essential to a devil, the love of evil in and for itself. But in the later theology it will be observed that evil in Ahriman is not organic.

The war being over and its fury past, the hostile chief is seen not so black as he had been painted; the belief obtains that he does not actually love darkness and evil. He was thrust into them as a punishment for his jealousy, pride, and destructive ambition.

And because that dark kingdom was a punishment—therefore not congenial—it was at length (the danger past) held to be disciplinary. Growing faith in the real supremacy of Good discovers the immoral god to be an exaggerated anthropomorphic egoist; this divine devil is a self-centred potentate who had attempted to subordinate moral law and human welfare to his personal ascendancy. His fate having sealed the sentence on all ambitions of that character, humanity is able to pardon the individual offender, and find a hope that Ahriman, having learned that no real satisfaction for a divine nature can be found in mere power detached from rectitude, will join in the harmony of love and loyalty at last.

Chapter 4. Viswámitra: The Theocratic Devil

Priestcraft in government means pessimism in the creed and despair in the heart. Under sacerdotal rule in India it seemed paradise enough to leave the world, and the only hell dreaded was a return to it. ‘The twice-born man,’ says Manu, ‘who shall without intermission have passed the time of his studentship, shall ascend after death to the most exalted of regions, and no more spring to birth again in this lower world.’ Some clause was necessary to keep the twice-born man from suicide. Buddha invented a plan of suicide-in-life combined with annihilation of the gods, which was driven out of India because it put into the minds of the people the philosophy of the schools. Thought could only be trusted among classes interested to conceal it.

The power and authority of a priesthood can only be maintained on the doctrine that man is ‘saved’ by the deeds of a ceremonial law; any general belief that morality is more acceptable to gods than ceremonies must be fatal to those occult and fictitious virtues which hedge about every pious impostor. Sacerdotal power in India depended on superstitions carefully fostered concerning the mystical properties of a stimulating juice (soma), litanies, invocations, and benedictions by priests; upon sacrifices to the gods, including their priests, austerities, penances, pilgrimages, and the like; one characteristic running through all the performances—their utter worthlessness to any being in the universe except the priest. An artificial system of this kind has to create its own materials, and evoke forces of evolution from many regions of nature. It is a process requiring much more than the wisdom of the serpent and more than its harmfulness; and there is a bit of nature’s irony in the fact that when the Brahman Rishi gained supremacy, the Cobra was also worshipped as belonging to precisely the same caste and sanctity.

There are traces of long and fierce struggles preceding this consummation. Even in the Vedic age—in the very dawn of religious history—Tetzel appears with his indulgences and Luther confronts him. The names they bore in ancient India were Viswámitra and Vasishtha. Both of these were among the seven powerful Rishis who made the hierarchy of India in the earliest age known to us. Both were composers of some of the chief hymns of the Vedas, and their respective hymns bear the stamp of the sacerdotal and the anti-sacerdotal parties which contended before the priestly sway had reached its complete triumph. Viswámitra was champion of the high priestly party and its political pretensions. In the Rig-Veda there are forty hymns ascribed to him and his family, nearly all of which celebrate the divine virtues of Soma-juice and the Soma-sacrifice. As the exaltation of the priestly caste in Israel was connected with a miracle, in which the Jordan stopped flowing till the ark had been carried over, so the rivers Sutledge and Reyah were said to have rested from their course when Viswámitra wished to cross them in seeking the Soma. This Rishi became identified in the Hindu mind for all time with political priestcraft. On the other hand, Vasishtha became equally famous for his hostility to that power, as well as for his profoundly religious character,—the finest hymns of the Vedas, as to moral feeling, being those that bear his name. The anti-sacerdotal spirit of Vasishtha is especially revealed in a strange satirical hymn in which he ridicules the ceremonial Bráhmans under the guise of a panegyric on frogs. In this composition occur such verses as these:—

‘Like Bráhmans at the Soma-sacrifice of Atirâtra, sitting round a full pond and talking, you, O frogs, celebrate this day of the year when the rainy season begins.

‘These Bráhmans, with their Soma, have had their say, performing the annual rite. These Adhwaryus, sweating while they carry the hot pots, pop out like hermits.

‘They have always observed the order of the gods as they are to be worshipped in the twelvemonth; these men do not neglect their season....

‘Cow-noise gave, Goat-noise gave, the Brown gave, and the Green gave us treasures. The frogs, who give us hundreds of cows, lengthened our life in the rich autumn.’[17]

Viswámitra and Vasishtha appear to have been powerful rivals in seeking the confidence of King Sudás, and from their varying fortunes came the tremendous feud between them which plays so large a part in the traditions of India. The men were both priests, as are both ritualists and broad-churchmen in the present day. They were borne on the stream of mythologic evolution to representative regions very different from any they could have contemplated. Vasishtha, ennobled by the moral sentiment of ages, appears as the genius of truth and justice, maintaining these as of more ‘merit’ than any ceremonial perfections. The Bráhmans, whom he once ridiculed, were glad enough in the end to make him their patron saint, though they did not equally honour his principles. On the other hand, Viswámitra became the type of that immoral divinity which received its Iranian anathema in Ahriman. The murder he commits is nothing in a personage whose Soma-celebrations have raised him so high above the trivialities of morality.

It is easy to see what must be the further development of such a type as Viswámitra when he shall have passed from the guarded pages of puranic tradition to the terrible simplicities of folklore. The saint whose majesty is built on ‘merits,’ which have no relation to what the humble deem virtues, naturally holds such virtues in cynical contempt; naturally also he is indignant if any one dares to suggest that the height he has reached by costly and prolonged observances may be attained by poor and common people through the practice of virtue. The next step is equally necessary. Since it is hard to argue down the facts of human nature, Vasishtha is pretty sure to have a strong, if sometimes silent, support for his heretical theory of a priesthood representing virtue; consequently Viswámitra will be reduced at length to deny the existence of virtue, and will become the Accuser of those to whom virtues are attributed. Finally, from the Accuser to the Tempter the transition is inevitable. The public Accuser must try and make good his case, and if the facts do not support it, he must create other facts which will, or else bear the last brand of his tribe—Slanderer.

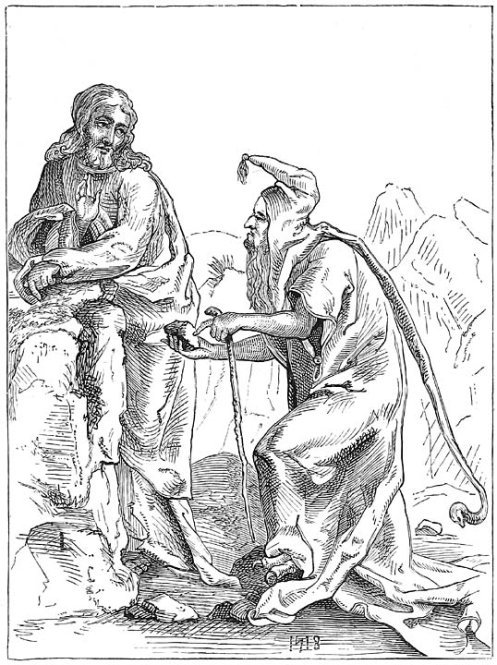

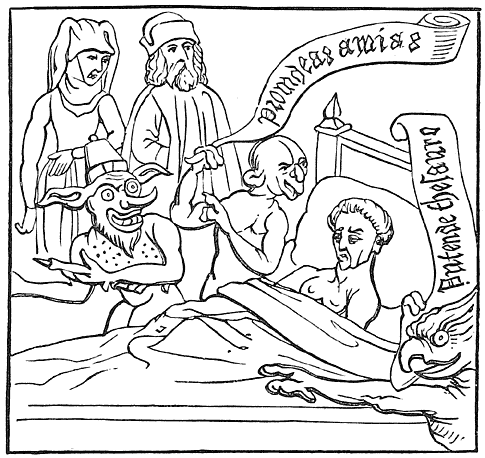

Leaving out of sight all historical or probable facts concerning Viswámitra and Vasishtha, but remembering the spirit of them, let us read the great Passion-play of the East, in which their respective parts are performed again as intervening ages have interpreted them. The hero of this drama is an ancient king named Hariśchandra, who, being childless, and consequently unable to gain immortality, promised the god Varuna to sacrifice to him a son if one were granted him. The son having been born, the father beseeches Varuna for respite, which is granted again and again, but stands firmly by his promise, although it is finally commuted. The repulsive features of the ancient legend are eliminated in the drama, the promise now being for a vast sum of money which the king cannot pay, but which Viswámitra would tempt him to escape by a technical fiction. Sir Mutu Cumára Swámy, whose translation I follow, presents many evidences of the near relation in which this drama stands to the religious faith of the people in Southern India and parts of Ceylon, where its representation never fails to draw vast crowds from every part of the district in which it may occur, the impression made by it being most profound.[18]

We are first introduced to Hariśchandra, King of Ayòdiah (Oude), in his palace, surrounded by every splendour, and by the devotion of his prosperous people. His first word is an ascription to the ‘God of gods.’ His ministers come forward and recount the wealth and welfare of the nation. The first Act witnesses the marriage of Hariśchandra with the beautiful princess Chandravatí, and it closes with the birth of a son.

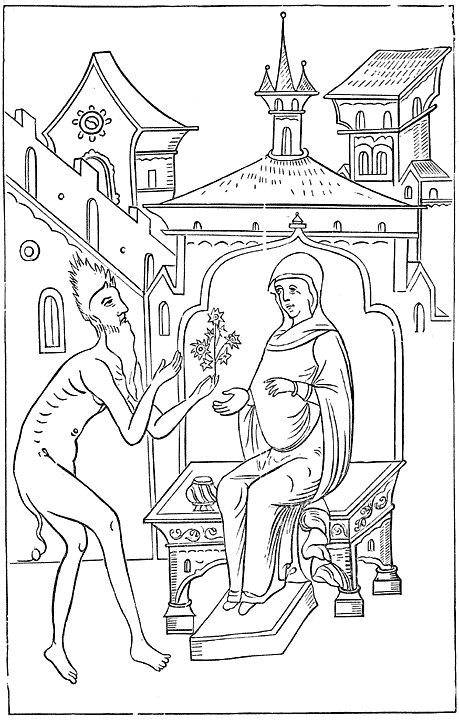

The second Act brings us into the presence of Indra in the Abode of the Gods. The Chief enters the Audience Hall of his palace, where an assembly of deities and sages has awaited him. These sages are holy men who have acquired supernatural power by their tremendous austerities; and of these the most august is Viswámitra. By the magnitude and extent of his austerities he has gained a power beyond even that of the Triad, and can reduce the worlds to cinders. All the gods court his favour. As the Council proceeds, Indra addresses the sages—‘Holy men! as gifted with supernatural attributes, you roam the universe with marvellous speed, there is no place unknown to you. I am curious to learn who, in the present times, is the most virtuous sovereign on the earth below. What chief of mortals is there who has never told a lie—who has never swerved from the course of justice?’ Vasishtha, a powerful sage and family-priest of Hariśchandra, declares that his royal disciple is such a man. But the more powerful Viswámitra denounces Hariśchandra as cruel and a liar. The quarrel between the two Rishis waxes fierce, until Indra puts a stop to it by deciding that an experiment shall be made on Hariśchandra. Vasishtha agrees that if his disciple can be shown to have told a lie, or can be made to tell one, the fruit of his life-long austerities, and all the power so gained, shall be added to Viswámitra; while the latter must present his opponent with half of his ‘merits’ if Hariśchandra be not made to swerve from the truth. Viswámitra is to employ any means whatever, neither Indra or any other interfering.

Viswámitra sets about his task of trying and tempting Hariśchandra by informing that king that, in order to perform a sacrifice of special importance, he has need of a mound of gold as high as a missile slung by a man standing on an elephant’s back. With the demand of so sacred a being Hariśchandra has no hesitation in complying, and is about to deliver the gold when Viswámitra requests him to be custodian of the money for a time, but perform the customary ceremony of transfer. Holding Hariśchandra’s written promise to deliver the gold whensoever demanded, Viswámitra retires with compliments. Then wild beasts ravage Hariśchandra’s territory; these being expelled, a demon boar is sent, but is vanquished by the monarch. Viswámitra then sends unchaste dancing-girls to tempt Hariśchandra; and when he has ordered their removal, Viswámitra returns with them, and, feigning rage, accuses him of slaying innocent beasts and of cruelty to the girls. He declares that unless Hariśchandra yields to the Pariah damsels, he himself shall be reduced to a Pariah slave. Hariśchandra offers all his kingdom and possessions if the demand is withdrawn, absolutely refusing to swerve from his virtue. This Viswámitra accepts, is proclaimed sovereign of Ayòdiah, and the king goes forth a beggar with his wife and child. But now, as these are departing, Viswámitra demands that mound of gold which was to be paid when called for. In vain Hariśchandra pleads that he has already delivered up all he possesses, the gold included; the last concession is declared to have nothing to do with the first. Yet Viswámitra says he will be charitable; if Hariśchandra will simply declare that he never pledged the gold, or, having done so, does not feel bound to pay it, he will cancel that debt. ‘Such a declaration I can never make,’ replies Hariśchandra. ‘I owe thee the gold, and pay it I shall. Let a messenger accompany me and leave me not till I have given him thy due.’

From this time the efforts of Viswámitra are directed to induce Hariśchandra to declare the money not due. Amid his heartbroken people—who cry, ‘Where are the gods? Can they tolerate this?’—he who was just now the greatest and happiest monarch in the world goes forth on the highway a wanderer with his Chandravatí and their son Devaráta dressed in coarsest garments. His last royal deed is to set the crown on his tempter’s head. The people and officers follow, and beg his permission to slay Viswámitra, but he rebukes them, and counsels submission. Viswámitra orders a messenger, Nakshatra, to accompany the three wretched ones, and inflict the severest sufferings on them until the gold is paid, and amid each ordeal to offer Hariśchandra all his former wealth and happiness if he will utter a falsehood.

They come to a desert whose sands are so hot that the wife faints. Hariśchandra bears his son in his arms, but in addition is compelled to bear Nakshatra (the Bráhman and tormentor) on his shoulders. They so pass amid snakes and scorpions, and receive terrible stings; they pass through storm and flood, and yet vainly does Nakshatra suggest the desired falsehood.

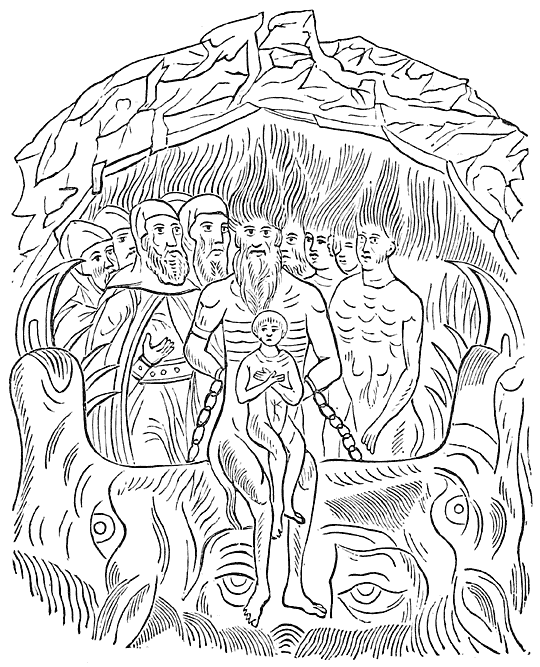

Then follows the ordeal of Demons, which gives an interesting insight into Tamil Demonology. One of the company exclaims—‘How frightful they look! Who can face them? They come in battalions, young and old, small and great—all welcome us. They disport themselves with a wild dance; flames shoot from their mouths; their feet touch not the earth; they move in the air. Observe you the bleeding corpses of human beings in their hands. They crunch them and feed on the flesh. The place is one mass of gore and filth. Wolves and hyænas bark at them; jackals and dogs follow them. They are near. May Siva protect us!’

Nakshatra. How dreadful! Hariśchandra, what is this? Look! evil demons stare at me—I tremble for my life. Protect me now, and I ask you no more for the gold.

Hariśchandra. Have no fear, Nakshatra. Come, place thyself in the midst of us.

Chief of the Goblins. Men! little men! human vermin! intrude ye thus into my presence? Know that, save only the Bráhman standing in the midst of you, you are all my prey to-night.

Hariśchandra. Goblin! certainly thou art not an evil-doer, for thou hast excepted this holy Bráhman. As for ourselves, we know that the bodies which begin to exist upon earth must also cease to exist on it. What matters it when death comes? If he spares us now he reserves us only for another season. Good, kind demon! destroy us then together; here we await our doom.

Nakshatra. Hariśchandra! before you thus desert me, make the goblin promise you that he will not hurt me.

Hariśchandra. Thou hast no cause for alarm; thou art safe.

Chief of the Goblins. Listen! I find that all four of you are very thin; it is not worth my while to kill you. On examining closely, I perceive that the young Bráhman is plump and fat as a wild boar. Give him up to me—I want not the rest.

Nakshatra. O Gods! O Hariśchandra! you are a great monarch! Have mercy on me! Save me, save me! I will never trouble you for the gold, but treat you considerately hereafter.

Hariśchandra. Sir, thy life is safe, stand still.

Nakshatra. Allow me, sirs, to come closer to you, and to hold you by the hand (He grasps their hands.)

Hariśchandra. King of the Goblins! I address thee in all sincerity; thou wilt confer on us a great favour indeed by despatching us speedily to the Judgment Hall of the God of Death. The Bráhman must not be touched; devour us.

The Goblin (grinding his teeth in great fury). What! dare you disobey me? Will you not deliver the Bráhman?

Hariśchandra. No, we cannot. We alone are thy victims.

[Day breaks, and the goblins disappear.]

Having thus withstood all temptation to harm his enemy, or to break a promise he had given to treat him kindly, Hariśchandra is again pressed for the gold or the lie, and, still holding out, an ordeal of fire follows. Trusting the God of Fire will cease to afflict if one is sacrificed, Hariśchandra prepares to enter the conflagration first, and a pathetic contention occurs between him and his wife and son as to which shall be sacrificed. In the end Hariśchandra rushes in, but does not perish.

Hariśchandra is hoping to reach the temple of Vis Wanàth[19] at Kasi and invoke his aid to pay the gold. To the temple he comes only to plead in vain, and Nakshatra tortures him with instruments. Finally Hariśchandra, his wife and child, are sold as slaves to pay the debt. But Viswámitra, invisibly present, only redoubles his persecutions. Hariśchandra is subjected to the peculiar degradation of having to burn dead bodies in a cemetery. Chandravatí and her son are subjected to cruelties. The boy is one day sent to the forest, is bitten by a snake, and dies. Chandravatí goes out in the night to find the body. She repairs with it to the cemetery. In the darkness she does not recognise her husband, the burner of the bodies, nor he his wife. He has strictly promised his master that every fee shall be paid, and reproaches the woman for coming in the darkness to avoid payment. Chandravatí offers in payment a sacred chain which Siva had thrown round her neck at birth, invisible to all but a perfect man. Hariśchandra alone has ever seen it, and now recognises his wife. But even now he will not perform the last rites over his dead child unless the fee can be obtained as promised. Chandravatí goes out into the city to beg the money, leaving Hariśchandra seated beside the dead body of Devaráta. In the street she stumbles over the corpse of another child, and takes it up; it proves to be the infant Prince, who has been murdered. Chandravatí—arrested and dragged before the king—in a state of frenzy declares she has killed the child. She is condemned to death, and her husband must be her executioner. But the last scene must be quoted nearly in full.

Verakvoo (Hariśchandra’s master, leading on Chandravatí). Slave! this woman has been sentenced by our king to be executed without delay. Draw your sword and cut her head off. (Exit.)

Hariśchandra. I obey, master. (Draws the sword and approaches her.)

Chandravatí (coming to consciousness again). My husband! What! do I see thee again? I applaud thy resolution, my lord. Yes; let me die by thy sword. Be not unnerved, but be prompt, and perform thy duty unflinchingly.

Hariśchandra. My beloved wife! the days allotted to you in this world are numbered; you have run through the span of your existence. Convicted as you are of this crime, there is no hope for your life; I must presently fulfil my instructions. I can only allow you a few seconds; pray to your tutelary deities, prepare yourself to meet your doom.

Viswámitra (who has suddenly appeared). Hariśchandra! what, are you going to slaughter this poor woman? Wicked man, spare her! Tell a lie even now and be restored to your former state!

Hariśchandra. I pray, my lord, attempt not to beguile me from the path of rectitude. Nothing shall shake my resolution; even though thou didst offer to me the throne of Indra I would not tell a lie. Pollute not thy sacred person by entering such unholy grounds. Depart! I dread not thy wrath; I no longer court thy favour. Depart. (Viswámitra disappears.)

My love! lo I am thy executioner; come, lay thy head gently on this block with thy sweet face turned towards the east. Chandravatí, my wife, be firm, be happy! The last moment of our sufferings has at length come; for to sufferings too there is happily an end. Here cease our woes, our griefs, our pleasures. Mark! yet awhile, and thou wilt be as free as the vultures that now soar in the skies.

This keen sabre will do its duty. Thou dead, thy husband dies too—this self-same sword shall pierce my breast. First the child—then the wife—last the husband—all victims of a sage’s wrath. I the martyr of Truth—thou and thy son martyrs for me, the martyr of Truth. Yes; let us die cheerfully and bear our ills meekly. Yes; let all men perish, let all gods cease to exist, let the stars that shine above grow dim, let all seas be dried up, let all mountains be levelled to the ground, let wars rage, blood flow in streams, let millions of millions of Hariśchandras be thus persecuted; yet let Truth be maintained—let Truth ride victorious over all—let Truth be the light—Truth the guide—Truth alone the lasting solace of mortals and immortals. Die, then, O goddess of Chastity! Die, at this the shrine of thy sister goddess of Truth!

[Strikes the neck of Chandravatí with great force; the sword, instead of harming her, is transformed into a string of superb pearls, which winds itself around her: the gods of heaven, all sages, and all kings appear suddenly to the view of Hariśchandra.]

Siva (the first of the gods). Hariśchandra, be ever blessed! You have borne your severe trials most heroically, and have proved to all men that virtue is of greater worth than all the vanities of a fleeting world. Be you the model of mortals. Return to your land, resume your authority, and rule your state. Devaráta, victim of Viswámitra’s wrath, rise! (He is restored to life.)

Rise you, also, son of the King of Kasi, with whose murder you, Chandravatí, were charged through the machinations of Viswámitra. (He comes to life also.)

Hariśchandra. All my misfortunes are of little consequence, since thou, O God of gods, hast deigned to favour me with thy divine presence. No longer care I for kingdom, or power, or glory. I value not children, or wives, or relations. To thy service, to thy worship, to the redemption of my erring soul, I devote myself uninterruptedly hereafter. Let me not become the sport of men. The slave of a Pariah cannot become a king; the slave-girl of a Bráhman cannot become a queen. When once the milk has been drawn from the udder of a cow nothing can restore the self-same milk to it. Our degradation, O God, is now beyond redemption.

Viswámitra. I pray, O Siva, that thou wouldst pardon my folly. Anxious to gain the wager laid by me before the gods, I have most mercilessly tormented this virtuous king; yet he has proved himself the most truthful of all earthly sovereigns, triumphing victoriously over me and my efforts to divert him from his constancy. Hariśchandra, king of kings! I crave your forgiveness.

Verakvoo (throwing off his disguise). King Hariśchandra, think not that I am a Pariah, for you behold in me even Yáma, the God of Death.

Kalakanda (Chandravatí’s cruel master, throwing off his disguise). Queen! rest not in the belief that you were the slave of a Bráhman. He to whom you devoted yourself am even I—the God of Fire, Agni.

Vasishtha. Hariśchandra, no disgrace attaches to thee nor to the Solar race, of which thou art the incomparable gem. Even this cemetery is in reality no cemetery: see! the illusion lasts not, and thou beholdest here a holy grove the abode of hermits and ascetics. Like the gold which has passed through successive crucibles, devoid of all impurities, thou, O King of Ayòdiah, shinest in greater splendour than even yon god of light now rising to our view on the orient hills. (It is morning.)

Siva. Hariśchandra, let not the world learn that Virtue is vanquished, and that its enemy, Vice, has become the victor. Go, mount yon throne again—proclaim to all that we, the gods, are the guardians of the good and the true. Indra! chief of the gods, accompany this sovereign with all your retinue, and recrown him emperor of Ayòdiah. May his reign be long—may all bliss await him in the other world!

*****************

The plot of this drama has probably done as much and as various duty as any in the world. It has spread like a spiritual banyan, whose branches, taking root, have swelled to such size that it is difficult now to say which is the original trunk. It may even be that the only root they all had in common is an invisible one in the human heart, developed in its necessary struggles amid nature after the pure and perfect life.

But neither in the Book of Job, which we are yet to consider, nor in any other variation of the theme, does it rise so high as in this drama of Hariśchandra. In Job it represents man loyal to his deity amid the terrible afflictions which that deity permits; but in Hariśchandra it shows man loyal to a moral principle even against divine orders to the contrary. Despite the hand of the licenser, and the priestly manipulations, visible here and there in it—especially towards the close—sacerdotalism stands confronted by its reaction at last, and receives its sentence in the joy with which the Hindu sees the potent Rishis with all their pretentious ‘merits,’ and the gods themselves, kneeling at the feet of the man who stands by Truth.

It is amusing to find the wincings of the priests through many centuries embodied in a legend about Hariśchandra after he went to heaven. It is related that he was induced by Nárada to relate his actions with such unbecoming pride that he was lowered from Svarga (heaven) one stage after each sentence; but having stopped in time, and paid homage to the gods, he was placed with his capital in mid-air, where eyes sacerdotally actinised may still see the aerial city at certain times. The doctrine of ‘merits’ will no doubt be able for some time yet to charge ‘good deeds’ with their own sin—pride; but, after all, the priest must follow the people far enough to confess that one must look upward to find the martyr of Truth. In what direction one must look to find his accuser requires no further intimation than the popular legend of Viswámitra.

Chapter 5. Elohim and Jehovah

The sacred books of the Hebrews bring us into the presence of the gods (Elohim) supposed to have created all things out of nothing—nature-gods—just as they are in transition to the conception of a single Will and Personality. Though the plural is used (‘gods’) a singular verb follows: the tendency is already to that concentration which resulted in the enthronement of one supreme sovereign—Jehovah. The long process of evolution which must have preceded this conception is but slightly traceable in the Bible. It is, however, written on the face of the whole world, and the same process is going on now in its every phase. Whether with Gesenius[20] we take the sense of the word Elohim to be ‘the revered,’ or, with Fürst,[21] ‘the mighty,’ makes little difference; the fact remains that the word is applied elsewhere to gods in general, including such as were afterwards deemed false gods by the Jews; and it is more important still that the actions ascribed to the Elohim, who created the heavens and the earth, generally reflect the powerful and un-moral forces of nature. The work of creation in Genesis (i. and ii. 1–3) is that of giants without any moral quality whatever. Whether or not we take in their obvious sense the words, ‘Elohim created man in his own image, ... male and female created he them,’ there can be no question of the meaning of Gen. vi. 1, 2: ‘The sons of Elohim saw the daughters of men that they were beautiful, and they took to themselves for wives whomsoever they chose.’ When good and evil come to be spoken of, the name Jehovah[22] at once appears. The Elohim appear again in the Flood, the wind that assuaged it, the injunction to be fruitful and multiply, the cloud and rainbow; and gradually the germs of a moral government begin to appear in their assigning the violence of mankind as reason for the deluge, and in the covenant with Noah. But even after the name Jehovah had generally blended with, or even superseded, the other, we find Elohim often used where strength and wonder-working are thought of—e.g., ‘Thou art the god that doest wonders’ (Ps. lxxvii.). ‘Thy way is in the sea, and thy path in the great waters, and thy footsteps are not known.’

Against the primitive nature-deities the personality and jealous supremacy of Jehovah was defined. The golden calf built by Aaron was called Elohim (plural, though there was but one calf). Solomon was denounced for building altars to the same; and when Jeroboam built altars to two calves, they are still so called. Other rivals—Dagon (Judges xvi.), Astaroth, Chemosh, Milcom (1 Kings xi.)—are called by the once-honoured name. The English Bible translates Elohim, God; Jehovah, the Lord; Jehovah Elohim, the Lord God; and the critical reader will find much that is significant in the varied use of these names. Thus (Gen. xxii.) it is Elohim that demands the sacrifice of Isaac, Jehovah that interferes to save him. At the same time, in editing the story, it is plainly felt to be inadmissible that Abraham should be supposed loyal to any other god than Jehovah; so Jehovah adopts the sacrifice as meant for himself, and the place where the ram was provided in place of Isaac is called Jehovah-Jireh. However, when we can no longer distinguish the two antagonistic conceptions by different names their actual incongruity is even more salient, and, as we shall see, develops a surprising result.